In the Studio with Photographer Jimmy Nelson

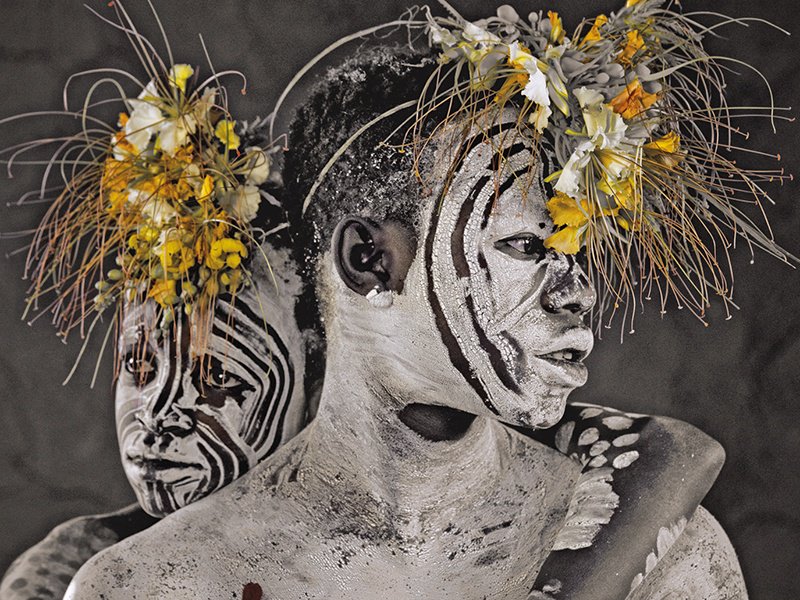

In a photographic journey that has seen him travel the globe, Jimmy Nelson has documented some of the world’s most remote – and endangered – indigenous tribes

In a photographic journey that has seen him travel the globe, Jimmy Nelson has documented some of the world’s most remote – and endangered – indigenous tribes

When Luxury Defined interviewed Jimmy Nelson, the photographer and photojournalist was – briefly – back in his studio, in the Netherlands, following years of traveling the world with his trusty old film camera. Born in the UK, in 1967, he has always been subject to wanderlust. When he left school in 1985, the teenage Nelson promptly went traveling – trekking the length of Tibet – before embarking upon his career in professional photography.

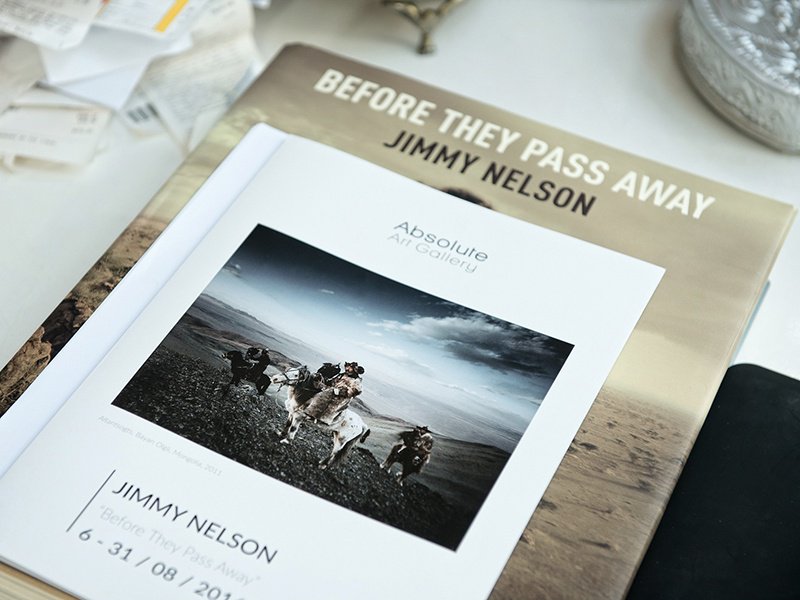

In 1992, Nelson was commissioned by Shell to produce the book Literary Portraits of China. This saw him spend three years in a country that relatively few Westerners get to see. Between 2010 and 2013, he traveled to the far corners of the earth for his work on little-known indigenous populations, resulting in Before They Pass Away – a book documenting age-old tribal traditions and unique, increasingly threatened ways of life.

What was the first photograph you ever took?

The first photograph I ever remember taking was when I was 17. It was on the journey I made when I basically ran away, and walked across Tibet – when I left school and was away for about a year and a half.

Tell us about your early years.

I was born in Kent [in south-eastern England]. Between the ages of one and seven, I lived abroad, in Africa – my father was a geologist who worked for Shell, and every year we would move to a different destination.

Although I was unaware of it at the time, my nomadic childhood – seeing the contrast between the developed and the undeveloped world – had a huge impact on me. After traveling, I spent 10 years at a boarding school; and then, at 16, my hair fell out, and at 17, I ran away.

So, being emotionally and physically a little bit disoriented, and having traveled a lot as a child, it all combined, I think, to become a catalyst for what I do now. I think, in hindsight, my hair fell out due to three factors: stress; I had cerebral malaria; and I was given the wrong medicine. I think it was the emotional stress of feeling abandoned and not having people to whom I could communicate my emotions… a nervous reaction.

Why did you decide to trek Tibet when you left school?

I wanted to run away. I wanted to go somewhere on the planet where I could find empathy with people who looked like me. It’s very simple: in Tibet there are lots of little bald boys running around monasteries as monks! As a child, I collected Tintin books, and I remember I’d seen the little bald boys in them. I didn’t go to Tibet to meet the Dalai Lama, or because I knew where it was, I just wanted to fit in.

That “process” went on for a year and a half. When I came back – much to everybody’s surprise – a few “happy snaps” that I’d taken along the way got published. I then earned a little bit of money and, with that money, I left again – and that’s essentially how I started [a career in photojournalism].

Simply to be free of any form of structure, institution, anybody… and to find a way to use my creative talents, which were looked down upon as a child. I didn’t excel in traditional forms of education, but I was always very comfortable with forms of creativity – but they weren’t always encouraged.

When did you become a photographer?

Good question. The first picture I published was when I was 19; I subsisted from photography up to the age of about 24; after that I began making a half-decent living out of it. That’s because I left photojournalism and moved into commercial photography.

How long did it take you to produce Before They Pass Away?

I’d say 80 to 90 per cent of the material was created over a period of four years. The other 10 to 20 per cent was that catalyst of what I’d been gathering in the years prior to that, but without any initial focus. The catalyst was generated by my own interest, and also the interest of other people. I then stopped working commercially and dedicated myself 100 per cent to the project.

From having spent the whole of my life traveling; seeing the extreme changes and how change was speeding up, due to the digitalization of the modern world. I’d visited most of the places I went for the project as a child; revisiting them as an adult – and seeing the speed with which these particular tribes or cultures were abandoning their heritage – was an important factor. As was a very self-indulgent wish to essentially paint these people with a camera, in a way that I’d never seen before; I felt they’d all been filmed and photographed before, but not “put upon a pedestal” of beauty, of iconography.

I was also inspired by someone who’s been a hero of mine for about 30 years – the 20th-century American photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis. He did the same kind of thing with Native Americans; for about 30 years, he traveled around North America, aesthetically, visually, artistically documenting [them] – making a cultural statement, saying: “We have to acknowledge them before they pass away.”

One highlight was discovering that the more extreme you go – in terms of isolation and culture – the more extreme you have to become in your form of finding a way of communicating, and the more empathy I found. The more I could be “Mr Bean with a tripod!” the more difficult the situation, the more remote, the more isolated, the colder – the more the connection was made.

A highlight since the book has been published is the enormous enthusiasm many people in the world seem to have for this approach to the subject matter, and how humbling and exciting that is. It’s something I’ve felt for many years, but could never put into a visual form or structure. The furthering of the project – having produced a book and exhibitions, and having an online forum – is extremely rewarding.

The more difficult the situation, the more remote, the more isolated, the colder, the more the connection was made – Jimmy Nelson

How do you actually make your photos?

Until now, I’ve been using a 50-year-old plate camera – because, very simply, the more complicated you make the making of the photograph, and the more you limit yourself in terms of the opportunities for when you can make that picture, the more extreme your emotions become in the focus. If I’d turned up at a location with a digital camera, the analogy I use is: “You can spray and pray.” You don’t even have to concentrate – you know you’ll end up with the shot. You end up taking thousands!

If you go with a camera that’s 50 years old, and you go to the middle of Papua New Guinea, with only 50 sheets of film – so only 50 opportunities to make a picture – you guarantee that, every time you press that shutter, there’s a hyper-focus and concentration, and contact between you and the subject matter.

Getting there, you become extremely emotional, and in that form of extreme emotion, you end up showing who you really are – your passion and dedication, your eccentricity, determination, and focus – and people take you very, very seriously. If you go in with a modern digital camera, it’s all very easy and you never truly show your vulnerable self. The more you fall, the more you cry, the more you panic – the more the subject “holds” you.

Essentially, I don’t take pictures; there’s no showing of any cameras. You just sit for hours, days, and, in some cases, weeks on the ground. You start with praising them. In a way, you start worshipping them, acknowledging them. And when that contact is made, and they can see that you are very vulnerable, and that they can do whatever they want with you, then you start introducing what you have in your box – this old camera – then you start focusing and, eventually, making the pictures.

What do you hope to achieve with your work?

Three things. The first is very narcissistic – to be able to carry on doing this until the day I die, because it makes me extraordinarily happy, and I find it very fulfilling. Secondly, to carry on enthusing and inspiring the people in the developed world as to how valuable these people and their culture are. And thirdly, to be able to go back to the majority of the places I’ve been to and tell them how extraordinary their culture is, and encourage them to find a way of emancipating themselves, so they can find a way of holding on to elements of it, while at the same time developing.

I’ve already started work [on a follow-up book]. If everything goes well, it will be published in 2018, and will feature another 35 different indigenous cultures and groups around the world – combined with returning to some of the places I’ve already been to. I’m working on it in conjunction with an international film that brings the discussion to a higher platform. So, rather than just being “Jimmy and his pretty pictures of indigenous cultures,” [the work will be asking] what, perhaps, does it mean to them and us? And what can be done about it? Adding a more questioning layer to the whole theme.

Where is home for you?

Home is Amsterdam… and an aeroplane! I think I spend a third of my time producing new material, a third of my time thinking and talking about the project, and a third of my time in Amsterdam. We also have a house in Ibiza. If I have time to relax, I spend it there.

Describe your home in Amsterdam.

It’s a family house. It’s chaotic, it’s hectic. I have three children in their late teens; [they] used to travel with me extensively, when they were younger. I have a very powerful, outspoken wife. I don’t necessarily have a lot of say in the house – no-one takes me particularly seriously! We have three dogs and a cat. It’s busy.

How does your family cope with your absences?

Very good question. In a positive way and a negative way. As they are getting older, it’s easier. There’s sometimes an element of anger. They are Dutch, so they’re very outspoken and direct. They tell me what they think – immediately! Sometimes they’re very happy I’m not around, and sometimes they miss me. I hear from other people that they admire what I’m doing, and that I inspire them – but I never hear that from them directly! My wife and I have been together for 25 years, and every month is a new month.

What do you like to do when you’re not behind a camera?

We spend time in Ibiza; I spend a lot of time in the water. We have a big, old Zodiac [boat] that we like to get out into the sea. I also thoroughly enjoy running; I try to run most days.

Who or what would be your dream subject to photograph?

Interestingly, I decided this summer that, once the majority of this current project is complete, I would like to build an outdoor studio in Ibiza for a summer. Much the same way that Richard Avedon did – he made a very famous book, In the American West, traveling around [and] photographing the destitute. The work became an iconographic document of humanity from a particular perspective.

I would like to do that in Ibiza. I find the humanity that turns up there every July and August extraordinary – as a contemporary tribe. Every form of human being turns up on the island. From the richest people on the planet to the poorest; the most creative, the most intelligent, the dumbest, the most athletic… I would like to make a portrait document of it.

Photography by Jimmy Nelson: © Before They Pass Away by Jimmy Nelson, published by teNeues, £100 ($122) – also available as a small-format edition, collector’s edition and collector’s edition XXL.